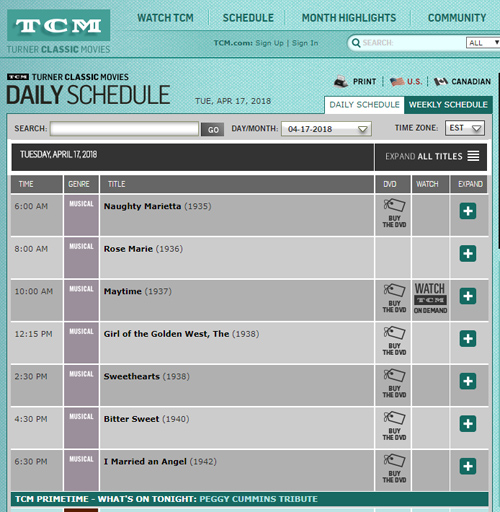

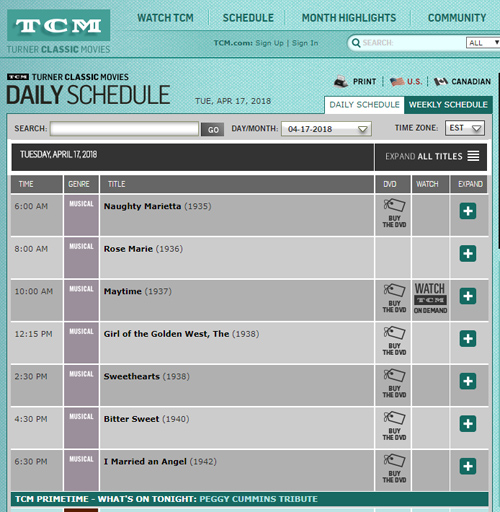

Alert! Watch live or set your DVRs! Turner Classic Movies is airing all the Jeanette MacDonald and Nelson Eddy team movies in chronological order starting at 6 am (Eastern Time) on Tuesday, April 17, 2018.

In recent weeks I’ve been chatting with folks on various Classic Hollywood groups and have come to realize that many people are not aware of the Jeanette-Nelson story or of the fascinating behind-the-scenes details of their 8 films together. It’s possible that no other screen team blurred their privates lives with their films as much as these two did. It surely was a case of reel life becoming real life…or vice versa! And an intriguing look at how Hollywood operated in the 1930s.

I will be live-blogging this entire marathon, detailing some of the following background information that adds to the enjoyment of these films:

- What was happening behind the scenes in their private lives that affected each production in terms of editing, deleted scenes and even whether the movie was in color or not!

- The story behind their most famous film, “Rose Marie” (1936) which was shot at Lake Tahoe when they were privately engaged and Nelson planned to elope with Jeanette in nearby Reno.

- Bloopers and ad-libbing such as Nelson shoving a startled Jeanette too hard into a chair in “Naughty Marietta,” (1935); pregnant Jeanette falling on a staircase in ”Sweethearts” (1938); Jeanette cracking up and breaking out of character at Nelson’s antics in “I Married An Angel” (1942).

- Why Nelson and Jeanette are both in tears in “Maytime” (1937) and why he predicted their lives would turn out like the plot of that film. Also, why he is visibly drunk in “The Girl of the Golden West (1938) and the main love duet is missing. In “Bitter Sweet” (1940) Nelson is thinner and looks weary in some scenes due to recovering from a breakdown. Additionally, why there are so few candids of them together from that movie as the studio had ordered them to squelch their renewed affair and stay away from each other off-camera.

- Audio recordings and related photos, candids, screenshots and “what to watch for” guides.

- Quotes and anecdotes relating to these 8 films… from or about the many co-workers or friends who granted me interviews and are quoted in my MacDonald-Eddy biography Sweethearts.

I will be happy to answer any questions I can about these films and will update this post later today with links of how to contact and read real-time updates.

The late, great TCM host Robert Osborne praised my book “Sweethearts” when it was first published, noting that it “offers considerable proof they may have been secret lovers for years.” I was also friends with Jeanette MacDonald’s actress sister Blossom Rock (grandmama in “The Addams Family”) who authorized me to write the biography because she felt her sister and Nelson Eddy were unfairly becoming forgotten when they were two of the hugest stars in the MGM galaxy…or in all of Hollywood!

For some reason “New Moon” (1940) is not included in this film marathon but can be streamed as a rental/purchase from iTunes and Vudu or purchased as a DVD from

shop.tcm.com or Amazon’s website. I am posting the “New Moon” article now for those who wish to watch it in advance…or at a later date. In fact, I will keep these posts up for anyone wanting to refer to them in the future.

Note that I am not affiliated with TCM. I have lectured on this film series at the American Film Institute (AFI East Coast), at film festivals, writers’s events, in school classes and on two dedicated MacDonald-Eddy cruises.

© Copyright 2018 by Sharon Rich. All rights reserved. All references and quotes to the book Sweethearts © Copyright 1994, 2001, 2014 by Sharon Rich

Happy May Day! Thanks to Cat Clark for this beautiful artwork.